Japanese delight in telling visitors is that “Japan has four distinct seasons.” You very likely come from a country that also has four distinct seasons but is less proud of the fact. So what does it mean, this puzzling meteorological observation? And more importantly, what’s the best time to visit Japan?

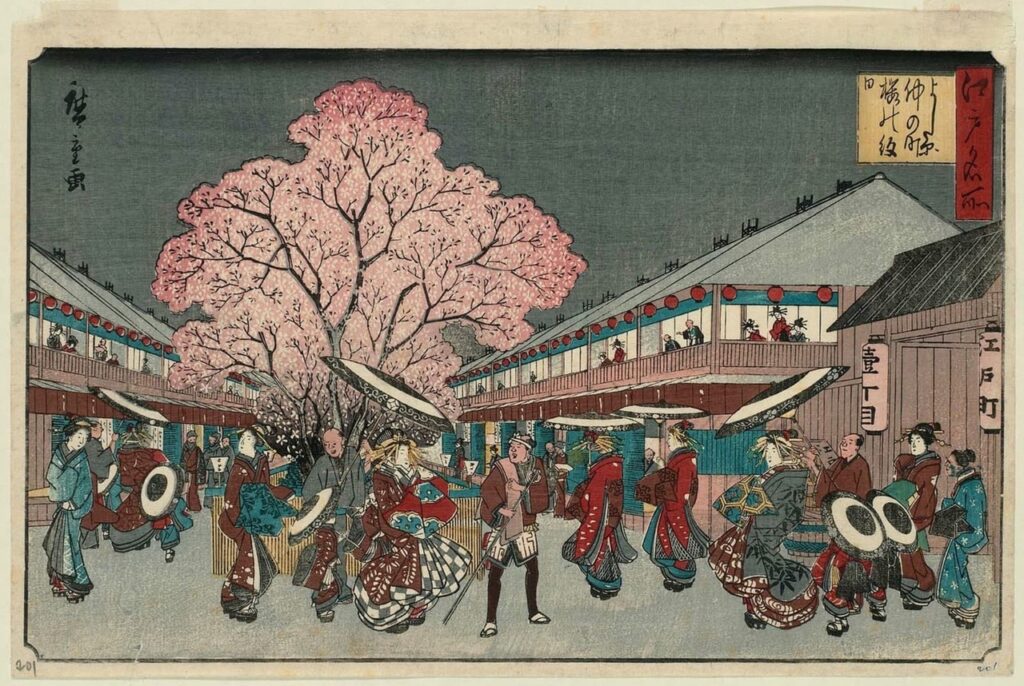

Well, the “four distinct seasons” boast probably comes from Japan’s long history of observing and celebrating the seasons in art. For centuries (millennia?) Japanese and Chinese artists have been recording the seasons in woodblock prints, paintings and poems, and even today in Japan people will hang a different scroll in each season (e.g. a snowscape in winter, plum or cherry blossoms in spring, autumn leaves or persimmons in autumn; the truly observant will note the warmer colours used in winter scenery versus the cooler colours for summer, as the scrolls and other decorations traditionally play a role in managing the temperature of the room they are in). In other words, Japanese are probably more aesthetically attuned (if only subconsciously) to the seasons than the average North American or European commuter scraping snow off his or her windscreen!

But which season is best for visiting Japan? Trick question: it depends on what you like, and in any event we’re fond of visiting places in several seasons, to compare and contrast.

Obviously cherry blossom season (springtime) is a “bucket list” event for many Japanophiles, and in Japan before and while the trees bloom the media publish hanami (cherry blossom viewing) trackers (so that domestic tourists can time their visits to destinations that are famous for their beautiful cherry trees). The weather during cherry blossom season should be excellent (post-winter warming is why the trees are blooming, after all!), and for centuries Japanese gardeners have been planting cherry trees in anticipation that they will be appreciated in the springtime. The only downsides are that 1) when exactly the cherries will be in full bloom depends on the weather in the preceding several months, making travel planning trickier; and 2) domestic travelers love cherry blossom season even more than visitors from overseas, meaning it can be a crowded time, during which public transport might be more efficient that chartered cars and coaches.

What about summertime? Summer is historically a popular time for leisure travel, with the kids out of school, and in Japan many people take a (short) holiday – often traveling back to their home towns – during Obon, a gravesweeping festival. Japanese are famous for not taking much holiday, so domestic tourism does not spike enormously during the summertime, which means hotels, restaurants and venues are particularly welcoming of international guest. But it can be hot and humid (like many places). Silver lining: that means we can eat more kakigori!

Autumn means autumn leaves, plus a bit of relief from the humidity. As is true with cherry blossom season, autumn is a wonderful time to appreciate the craft of the Japanese gardener. Japanese maples and gingko trees are especially rewarding during this season, and as the temperatures drop, we start thinking about switching from lighter summer fare to comfort food (and roasted chestnuts!).

Finally, winter. Yes, “winter is coming”, and don’t tell anyone, but winter is our favorite season in Japan. Of course the snow in Hokkaido is famous, but often there’s also good snow (and far fewer people) in the Japan Alps around Nagano. If you’re not a snowsports person, another great thing about winter in Japan is the lower humidity, not-so-low temperatures, and very often, clear skies. The views of Mount Fuji are the best at this time of year (in summertime very often you can’t see Mount Fuji from Kamakura due to humidity in the air). Also, many Japanese cities are good for walking, and winter is a great time to do that without having to change your shirt every 20 minutes!

So, yes, “four distinct seasons”, all of which have distinctive charms. Let us know if you have questions!

Postscript: If you’re interested in diving deeper into the world of ukiyo-e and Japanese art, Japan is – perhaps obviously – the best place to do so. There are hundreds of interesting small museums dotted around the country, and the large and well-known ones are well worth your time if you’re a culture vulture. We’ll post more soon about some of these fantastic resources.