On 1 January 2024, an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.5 on the Richter scale (and an intensity of shindo 7 – the maximum – on the Japanese scale) struck just off the coast of the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. Over one thousand aftershocks of lesser intensity followed, as well as a tsunami that reached over 6 metres in height in some places. As we write this, the death toll from the earthquake and tsunami is over 200, hundreds were injured, and additional scores remain missing.

On 11 March, 2011, of course, a much larger earthquake struck Japan – the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in the country, and the fourth most powerful earthquake recorded globally since modern seismography began in 1900. The ensuing tsunami reached over 40 metres in height in some places, and over 20,000 people died.

Japan is located on Asia’s “Ring of Fire”, which encircles most of the Pacific Ocean, from Chile to Indonesia, and contains anywhere from 750-900 volcanoes.

So should you worry about your safety if you’re planning a trip to Japan?

Well, 127 million people live in Japan, and for the most part, rather than worry, they take precautions. As you should do wherever you live – against storms, tornadoes, wildfires, and other natural disasters.

The most important thing to know about getting caught up in an earthquake in Japan is that the country has the world’s most stringent building regulations. Safety measures built into tall buildings include extra steel bracing, giant rubber pads and embedded hydraulic shock absorbers.

During the 2011 earthquake, which remember, was the fourth most powerful earthquake ever recorded, not one tall building collapsed (and very few other structures collapsed).

So what should you do?

If you’re inside a building, stay inside. Shelter under a table or a desk, or in a doorway. Sit rather than stand.

If you’re outside, move into open space. Don’t shelter near buildings or anything that might fall on you. Again, sitting is likely to be more comfortable than standing.

If you’re driving, come slowly and carefully to a stop, and stay inside your car. Don’t stop on a bridge or under an overpass. Don’t stop in a place where other things might fall on your car. When the shaking stops and you resume driving, be careful of cracks in the road and other hazards.

If you are near the ocean, listen for recorded warnings (accompanied by sirens) about possible tsunamis (you won’t miss them, and they will also be in English). Every coastal area has clearly marked tsunami evacuation points, and if you look, you will be able to find signage directing you to them. Japanese around you will be delighted to help you, even if their English is not great.

So what are some other practical steps you can take to be prepared in the event of a natural disaster (not only in Japan)?

• Travel with a mobile phone powerbank, and keep it charged

• Keep your important documents on you, and in your hotel, keep them in a handy place so you can easily grab them if you have to evacuate in a hurry

• Similarly, keep important medication in a handy place, so you can grab and go

• Bear in mind that in the aftermath of a disaster, you may not have access to electricity for several days; if so, you will want to ration your use of your mobile phone

• Japan’s disaster response mechanism is well-developed; if you are in a remote area, don’t panic – help will arrive

• The important things – water and food – are widely available throughout Japan; for example, there is a convenience store in every community (and thousands in the big cities). These businesses are historically among the first to resume operating after a disaster, even during local and regional power failures, with generator power

• But to tide you over for the first 24 hours, keep snacks on hand – in your bag and in your room

• Consider travel insurance, which is useful not only in the event of a disaster but in case of more ordinary travel-related hassles such as flight cancellations, lost luggage and illness

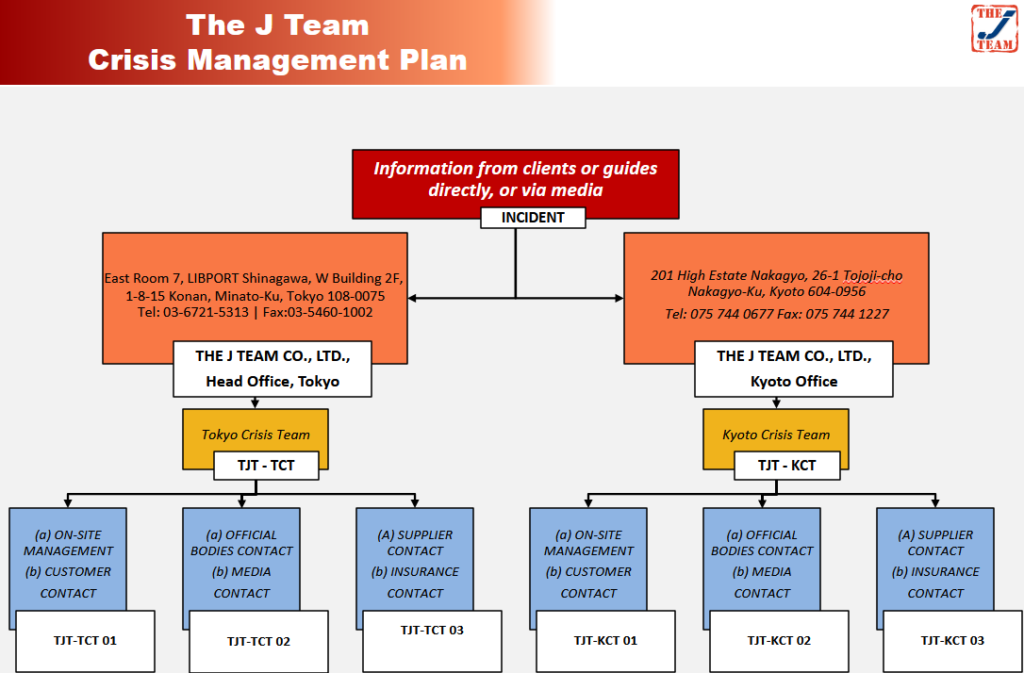

“Be prepared”, as the Boy Scouts say, and we at THE J TEAM are constantly updating our crisis and disaster preparedness procedures. During the month since the Hokuriku earthquake, we have spent considerable time renewing our preparedness procedures and updating our first aid skills. We recommend asking your DMC about their destination risk-assessment and preparedness procedures, as part of your event planning.

Millions of people travel to Japan every year and never encounter a problem, but it’s always best to be prepared. Be flexible. Stay calm. Don’t worry!